Rural India’s Skin Bank Crisis: 10 Things You Should Know About Access and Equity

A mother sits beside her 12-year-old son in a government hospital burn unit in rural Tamil Nadu. The boy was injured in a cooking fire accident three days ago. His burns cover 40% of his body. The doctor explains that skin grafts could save his life and restore his future: but the nearest functional skin bank is 300 kilometers away in Chennai. The family doesn’t have the means to travel, and even if they did, there’s no guarantee that donated skin would be available.

This is not a rare story. It happens every single day across rural India, where the gap between life-saving medical technology and actual patient access creates a crisis that touches millions of families.

1. The Numbers Tell a Devastating Story

Each year, over 7 million Indians suffer burn injuries. Rural areas account for nearly 70% of these cases, yet they have access to fewer than 10% of the country’s skin banks. Government Rajaji Hospital in Madurai: one of the larger rural medical centers: receives only 5-6 skin donors per year while treating 10-15 burn patients annually. This disparity means that most rural burn victims never receive the skin grafts that could transform their recovery and restore their lives.

The math is stark: one deceased donor can provide 15-18 sheets of skin, potentially helping up to 50 patients. But when donation rates remain this low, even well-equipped hospitals operate far below their life-saving potential.

2. Infrastructure Delays Create Years-Long Gaps in Care

Building a skin bank isn’t just about medical equipment: it’s about sustained commitment to implementation. Gujarat’s experience reveals the systemic delays that plague rural healthcare infrastructure. Two public sector skin banks announced with great fanfare faced three-year delays each before opening. Rajkot’s facility, announced in January 2020, finally opened in January 2023. Ahmedabad’s skin bank, announced in January 2021, began operations only in March 2024.

These aren’t just administrative delays. Every month of postponement represents lives lost, families shattered, and communities left without critical care. During those three years, how many burn victims in Gujarat’s rural districts suffered without access to skin grafts?

3. High Maintenance Costs Force Closures

Even when rural skin banks do open, keeping them operational presents enormous challenges. A skin bank that closed in 2019 during the pandemic shut down specifically due to high maintenance costs combined with poor donor response. The specialized refrigeration systems, sterile processing equipment, and trained technicians required to preserve and prepare skin grafts demand consistent funding and technical support.

Rural hospitals often struggle to justify these expenses when donor rates remain low and patient volumes can’t sustain the operational costs. This creates a vicious cycle: without functional skin banks, awareness doesn’t grow, and without awareness, donor numbers stay low.

4. Geographic Concentration Leaves Vast Areas Underserved

India’s skin banks remain heavily concentrated in major urban medical colleges and metropolitan hospitals. While cities like Mumbai, Delhi, and Chennai have multiple facilities, entire states have one or two skin banks: or none at all. Kerala established its first skin bank only recently at Government Medical College Hospital in Thiruvananthapuram.

This geographic inequity means that rural populations in underserved states face impossible choices: travel hundreds of kilometers to urban centers (often beyond their financial means) or go without life-saving treatment. The concentration of resources in urban areas perpetuates a two-tier healthcare system where your postal code determines your access to healing.

5. Limited Treatment Volumes Despite Critical Need

Even where rural skin banks operate successfully, they serve relatively small patient populations compared to the actual need in their regions. Rajkot Civil Hospital’s skin bank processed 62 donations benefiting more than 250 patients over two and a half years. Ahmedabad’s facility handled 26 donations for 11 patients in its first year and a half.

These numbers, while meaningful for the individual lives saved, represent a fraction of the burn victims in Gujarat’s rural districts. The limited treatment volume suggests that awareness, accessibility, or operational capacity (or all three) continue to constrain the reach of these facilities.

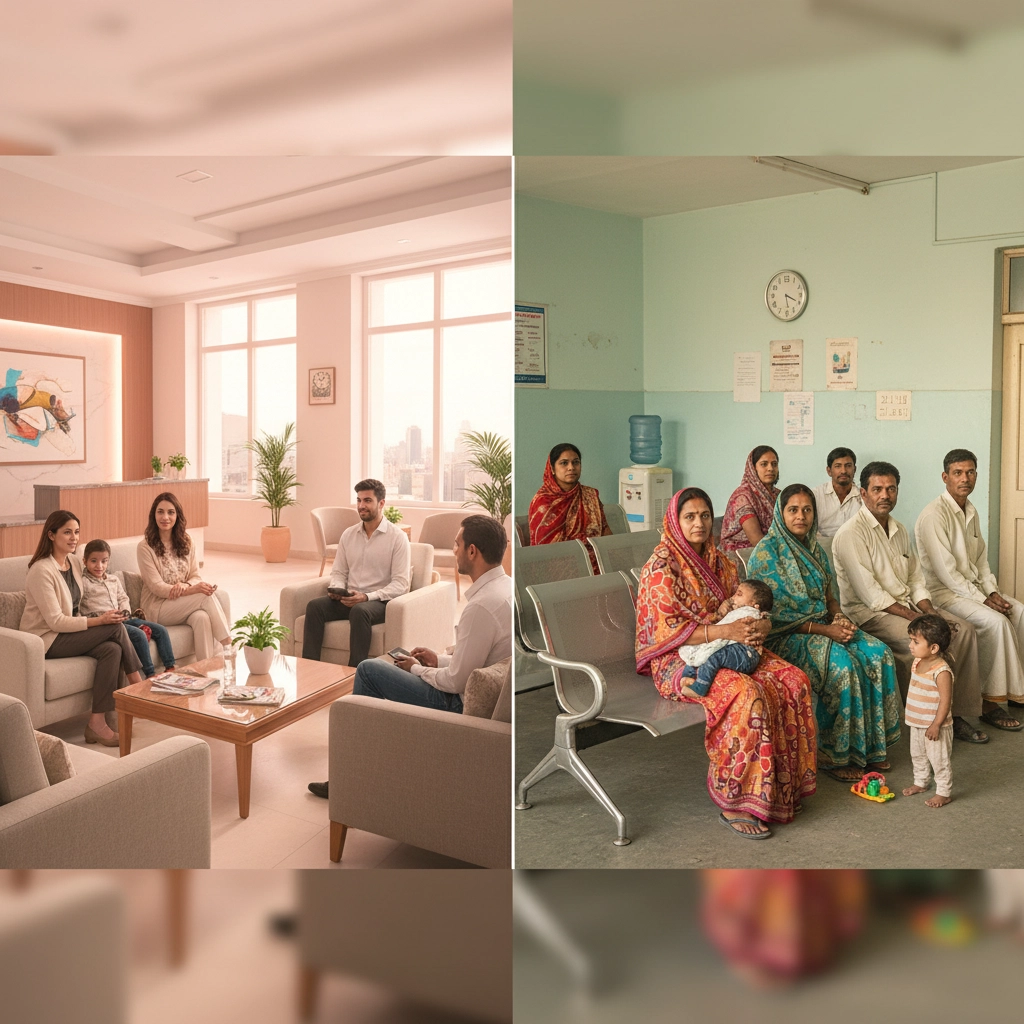

6. Private Healthcare Advantage Deepens Inequality

The gaps in public sector skin banks create an unintended benefit for private hospitals. Health activists warn that as public facilities struggle with donor recruitment and infrastructure maintenance, patients with financial resources increasingly turn to private healthcare for burn treatment and skin grafts.

This market dynamic creates a two-tier system where your economic status determines not just the quality of your burn care, but whether you receive skin grafts at all. Rural families: already facing transportation costs, lost income, and extended hospital stays: find themselves priced out of life-saving treatments available to urban, affluent patients.

7. Community Awareness Remains Critically Low

Perhaps the most solvable: yet persistent: challenge is the lack of community awareness about skin donation. Many rural families have never heard that skin donation is possible, beneficial, or respected within medical ethics. Others harbor misconceptions about the donation process or believe that cultural or religious concerns prevent participation.

Doctors and activists advocate for dedicated counseling teams to create awareness and encourage families of deceased individuals to consider donation. Without proper education and culturally sensitive counseling infrastructure, the pool of potential donors remains largely untapped, even in areas with functional skin banks.

8. Emergency Situations Expose Systemic Failures

Fire tragedies and mass casualty events starkly reveal the inadequacy of rural skin bank infrastructure. Seasonal surges during Diwali (due to firecracker accidents), industrial fires, and domestic cooking accidents create sudden spikes in demand that overwhelm existing systems.

Kerala’s experience with the Puttingal fireworks tragedy in 2018, combined with various fire incidents, exposed the desperate need for adequate skin bank infrastructure during emergencies. When multiple burn victims require immediate care simultaneously, the shortage of readily available skin grafts becomes a matter of life and death: not just for individuals, but for entire communities affected by tragedy.

9. Recent Progress Shows What’s Possible

Despite these challenges, meaningful progress is happening in select regions. Gujarat’s functional skin banks demonstrate that once established and properly supported, these facilities can achieve significant impact. Cumulatively, the state’s facilities have helped over 261 patients across two locations.

Kerala’s first skin bank received approval from the Kerala State Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisation and is expected to become operational soon. The Indian Army has launched specialized skin bank facilities, though these primarily serve military personnel rather than rural civilian populations.

These success stories prove that the infrastructure can work: but they also highlight how much remains to be done across the vast rural landscape.

10. Standardization Could Accelerate Progress

One promising development is the move toward standardized treatment protocols and operational guidelines. Kerala announced that standardized treatment protocols for burns units would be introduced, along with enhanced intensive care facilities for treating patients with burns exceeding 20% of their body.

Standardization addresses a key challenge: ensuring that rural skin banks operate with the same quality, safety, and efficiency as urban facilities. When every skin bank follows proven protocols for procurement, processing, storage, and transplantation, patient outcomes improve and operational sustainability increases.

This approach could accelerate the expansion of skin banks by reducing the learning curve for new facilities and creating systems that can be replicated across different rural contexts.

The Path Forward: Systems, Not Miracles

Rural India’s skin bank crisis is solvable, but it requires systematic action across multiple fronts. The cure is not a miracle; it is a system that connects awareness to infrastructure, donor families to recipient patients, and rural communities to urban medical expertise.

For Healthcare Systems: Prioritize skin bank development in district hospitals, not just medical colleges. Establish regional networks that allow rural facilities to share resources and expertise.

For Communities: Champion awareness campaigns that normalize skin donation and connect it to local values of service and compassion. Train local health workers to counsel families sensitively about donation options.

For Citizens: Visit Skin’d India to learn about skin donation and make your pledge. Share information with your networks, especially those in rural areas who may never have heard about this opportunity to save lives.

For Policymakers: Fund sustained operations, not just infrastructure announcements. Create incentive systems that reward consistent performance and community engagement in rural skin banks.

Every family facing a burn injury crisis deserves the same access to healing that skin donation provides. Rural India’s children, parents, and grandparents deserve the same second chances at life, dignity, and hope that urban patients can access.

The question isn’t whether we can solve this crisis. The question is whether we will choose to act with the urgency that millions of rural families desperately need.

Learn more about skin donation and pledge your support at skindindia.com. Follow our work on social media @skindindia.